Sven Anders HEDIN (Stockholm, 1865-1952) est

explorateur, notamment en Asie centrale, où il exerce ses talents de

géographe et topographe pour la réalisation de cartes (le Tibet par

exemple), et de photographe pour enrichir principalement ses propres

ouvrages.

Mais en 1914-1915, Hedin devient correspondant de guerre : ses

reportages pro-allemands lui valent d'être honoré par la maréchal

Hindenburg, mais rayé de la liste des membres de la Société géographique

royale britannique. Ils sont traduits en allemand à Leipzig en 1915 sous

le titre « Ein Volk in Waffen », et à Londres la même année sous le

titre « With the German armies in the West ».

Dans cet ouvrage, il conclut son reportage sur le front de l'ouest, par

une journée à Barbas, accompagnée de quelques prises de photographies, ce

5 novembre 1914. |

|

|

|

With the German armies in the West

Sven Hedin

Londres - New-York - 1915

CHAPTER XXIV

A FINAL DAY ON THE WESTERN FRONT

Needless to say the human alarums at the hotel forgot to call me in the morning,

but happily I awoke without their aid and dressed quietly as a mouse so as not

to disturb Duke Adolf Friedrich. Thereupon I wandered off in the pitch-dark

night with no other weapons than my Zeiss glasses and my camera to the

Europaïscher Hof, where the others were already assembled. I was asked to join

the party in the car driven by Tauchnitz, and already occupied by Captain

Kriebel and Lieut. Baron von Peihmann, both attached to the General Command of

the Falkenhausen army.

Our road took us south-eastward via Chateau-Salins in German Lorraine. We

crossed into France further south at Rixingen.

It was 7 o'clock when we started off. Day was just beginning to break, but the

sky looked threatening, the weather was most unpleasant, and a thin layer of

clayey mud lay over the hard surface, making the road as slippery as soap. My

two companions inside were as agreeable and as light-hearted as all other German

officers whom I had met. As we were skimming along, the pretty and interesting

country we were passing through was being explained to me on the map. We were

only a few kilometres from Rixingen when one of the pipes of the engine broke,

and the car absolutely refused to move another inch. However, providence has

presented us with legs, and so after walking a short distance we came upon a

motor-driven hospital wagon, on the roof of which we made ourselves comfortable.

We were soon to find that this motor conveyance was not without its dangers, for

the wagon skidded about terribly on the slippery road and threatened any moment

to dive into the ditch. However we held ourselves ready for any emergency so as

at least to fall feet foremost when the catastrophe came. In the end we managed

to get to Rixingen and reached the commandant's office just as the wagon began

skidding so hopelessly that the back wheels took command and the whole

bag-of-tricks was on the point of overturning. Our somewhat eccentric entry into

Rixingen aroused violent mirth from all who happened to be about. Here, however,

we secured a third car and drove on gaily to Blamont.

On leaving the village to the southward, the road turned up a hill to a slight

eminence, the right-hand side of which was wooded. In a field immediately to the

north of the little wood and evidently concealed by its trees, stood a battery,

which was thundering away for all it was worth. It was really a very impressive

sight to watch the guns firing their salvos.

The officer in charge gave his orders in a loud voice according to the

information received from the observing station. Then followed the usual brief,

brisk words of command : “Load ! Ready !! Fire !!!” The target for the moment

was the village of Ancerviller, situated about 5600 metres south of Blamont.

As the gun is discharged a sheaf of fire issues from the muzzle and a white

smoke cloud forms several metres in front.

In order not to attract the attention of the enemy, instructions have been given

that the battery must only be approached on foot. On the crest of the hill stood

the local commanding officer, Lieut.-Gen. von Tettenborn, acting Adjutant-General

to the King of Saxony, surrounded by his staff, some twenty officers. He was a

powerfully built little man with steel-grey hair and moustache. Hung over his

shoulders he carried a light brownish-grey cape with red collar and on his head

he wore a helmet with a grey cloth cover. Reports kept pouring in regarding the

progress of the action. Now it was a horseman, now a motor-cyclist, now a car

that came tearing along at full speed with information, whilst orders were sent

out with equal rapidity to the various fighting units.

General von Tettenborn received me with the greatest kindness and we stood

chatting awhile on the hill as if there had been no war within a hundred miles.

I was also introduced to all the other officers and in two minutes I felt

thoroughly at home. The general atmosphere here was exactly the same as I have

had occasion to record and admire all along the front, calm, reliant and

cheerful in the consciousness of the monstrous strength of the German army.

Two kilometres south of Blamont and about half that distance from the point

where we were standing, lies the little village of Barbas in a picturesque

hollow, its church tower dominating in a lordly manner the pretty little red-roofed

stone houses beneath. One and a half kilometres south of Barbas, sharply

outlined against the light rising background, were two little dark clumps of

trees. On the north side of these coppices two German batteries were actively

shelling the enemy positions. On the western border of the wooded belt to the

right infantry fighting was in actual progress. At the moment the Germans were

proceeding to the attack of the French positions. Both sides had concealed

themselves gingerly behind trees and bushes, but the rattling fire from rifles

and machine guns was deafening. One moment the shots would succeed one another

in a continuous din, the next minute one heard but isolated reports. Of the

actual fighting itself we saw nothing, but it became evident in the course of

the day that the centre of activity was shifting south-westward, which meant

that the German attack was progressing.

Behind us the battery at which we had just stopped kept pounding away, and once

more we heard the horrible, sinister whistle of shells pass overhead. The German

artillery was very active, but the French did not reply to the fire. Towards the

afternoon the German fire also ceased, the attempted goal having been reached.

It was assumed that the French batteries, which had but lately occupied this

point, had now been removed to some other place where they would come in more

useful. I for my part was quite content to do without their fire, and it was a

pleasant and restful experience not to have to be in constant dread of a shell

coming on the top of me.

The day before the French had sent a couple of shells into Blamont, but without

doing any appreciable damage. Neither did we see any aviators on this occasion.

I was told that they were less numerous in these parts.

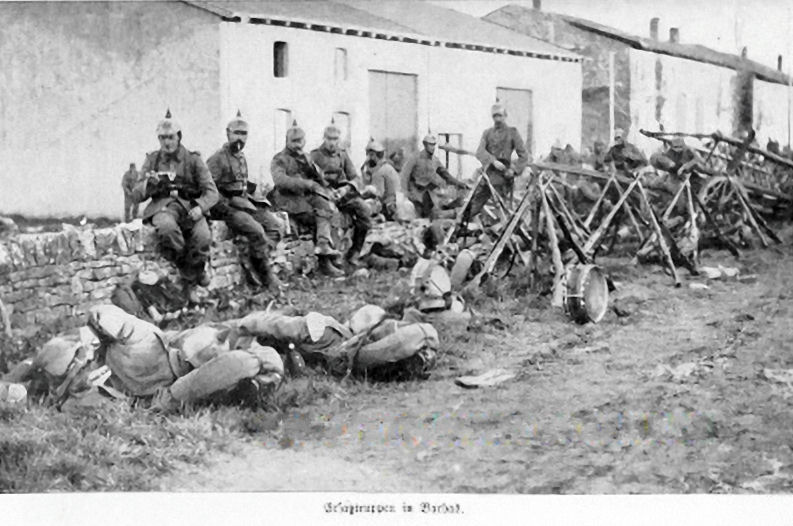

After a short visit to Blamont cemetery and a walk through the pretty village,

where we dined, I returned with a couple of officers to the hill, but found it

deserted. The General and his Staff had, it appeared, advanced a couple of

kilometres to Barbas, where we found all the officers assembled in an open space,

a cross between a street and a market-place. This had now become the point from

which the operations on the whole front of the division were directed, and

horsemen and cycle-orderlies kept dashing backwards and forwards as before on

the hill.

I remained at Barbas for another four hours and took the last photographs

destined to appear in this book. Wherever I turned, I found picturesque and

warlike subjects for my camera. In the open space referred to, officers with

maps in hand stood gathered in little groups. Outside a house, several horses

stood ready for the orderlies. In the next street, which was part of the great

main road, an ammunition column had halted. It extended from one end of the

village to the other and a bit beyond as well. The wagons were crowded with

artillerymen, full of life and in good spirits as usual, and they usually asked

for a photograph when I came along with my camera. On the fore-carriage of a gun

sat a man fast asleep. In the outskirts of the village two companies of reserves

had halted and were evidently waiting to take their place in the firing line.

“How are you, boys ?” I asked.

“Oh, first-rate, but it's a nuisance to have to lie and wait like this."

"What are you waiting for ?"

"Why to go ahead and fight, of course."

Here I found a chaplain, a strikingly humorous and amusing man, who knew

thoroughly how to get on with the soldiers ; but then he had been in war before,

in Pekin and German South-West Africa. As we stood chatting on the road, we were

gradually surrounded by a narrowing circle of grey jackets, who listened

intently to what we had to say. In the end they must have numbered fully 150,

and there, in the centre, stood the pastor throwing out jests and calling them

his grey field-mice, and they all laughed gaily at his whimsical ideas.

"What do they do for a living in peace time, I wonder, all these soldiers ?" I

asked.

"Oh," said the pastor, "there are all sorts, loafers and county councillors,

blacksmiths and professors, all jumbled together.

"What is your occupation, my lad ?" he asked of one who stood near, as he seized

him by the collar.

"Lecturer," he answered.

"What subject ?"

"Comparative philology of modern European languages."

"Excellent ! There you see, doctor, what use the philology of modern European

languages can be put to !"

"And what are you ?"

"Metal worker at Siemens and Halske's."

"And you ?"

"Village schoolmaster."

"And you ?"

"Navvy."

"And you ?"

"Professor of zoology."

"There you see the levelling effects of war. No trace of class distinction. They

all lie side by side in the trenches, eat the same food and are comrades through

thick and thin, and the professor is no better treated than the navvy."

"How many of you are keeping diaries of your war experience ?" I asked.

"I don't write a line," said one, standing with his hands in his pockets in

front of the circle.

"Why not ?"

“There are plenty of them who do as it is."

"Nonsense, you are a lazy beggar," says the pastor.

"All who keep diaries, put up their hands," said I, and a perfect forest of

hands rose into the air.

"Perhaps it will be simpler if those who don't keep diaries put up their hands."

They did so, and there were ten out of fully 150. What a monument of memories

and impressions, of wild adventures and heroic deeds told in simple and honest

words must they not represent, these diaries, written from day to day between

the fights, in the trenches and by the light of the bivouac fires !

To conclude, I asked in a loud voice although it was a stupid thing to do and I

ought to have known better - infandum jubes renovare dolorem : "How many of you

are social democrats ?"

At this there was a shout of laughter, almost of derision, and I suddenly felt

exceedingly awkward and wished I were back at Metz again. Even the pastor

laughed and shook his head. At last a burly-looking soldier answered for himself

and the others :

"There are no social democrats any more. There are nothing but German soldiers."

I made a desperate attempt to cover my retreat by saying : "Of course, of

course, I know ; but are there any among you who have been social democrats ?"

Some shouted no, others shrugged their shoulders and one replied : "Even if

there have been social democrats among us, all that rot has been washed away by

now. It is real and serious business we are dealing with now, and none of that

kids' game !"

Presently the men were ordered to form up and the circle melted away, leaving me

alone with the divisional pastor and three young officers with whom I chatted

for a few moments.

Then I went back to my friends and travelling companions from Metz. The day's

work was over. The result of the achievements of the day had been reported to

the General in Command, but they had to wait at Barbas until fresh orders

arrived, which might not be until midnight. For my part I could return to Metz

whenever I wanted to.

The sun had long since set when Captain Kaufmann came up and offered me a seat

in his car. He was a fine fellow and had moreover many memorable and interesting

things to tell me from his experiences in the war. So I said good-bye to my

charming host for the day, General von Tettenborn, and the other officers,

jumped up beside Kaufmann and a lieutenant and in a second we were on the way,

eating up the ninety kilometres separating us from our destination in the north-west.

We had our head-lamps lighted. At least twenty times we were stopped by the

patrols guarding the road, who swung their lanterns across the road and shouted

"halt ! " I consider we were very fortunate to get through with a whole skin,

for if one overlooks a single sentry, it is all up and one gets a bullet through

the back. There were numerous cavalry patrols about, evidently on their way home

after their scouting in the gloaming. They, too, were stopped by the pickets,

for otherwise French patrols in German uniforms might easily infest the roads

and villages held by the Germans. We were also stopped on entering and leaving

every village.

However, at last we got safely back to Metz, and thus ended my last day at the

front.

Notes : si la “dernière image du front de l'ouest” ci-dessus est prise à

Barbas ce 5

novembre 1914, alors la suivante, pourtant classée dans le chapitre VII, l'est

aussi :

|