The story of the Rainbow division

Raymond S. Tompkins

New York 1919

Note : s'il est indéniable que le soutien des troupes américaines a

contribué à la défense des lignes du secteur de Lunéville, on peut regretter

dans le texte ci-dessous la version malheureusement erronée d'un agrément

tacite de non agression entre les soldats français et allemands...

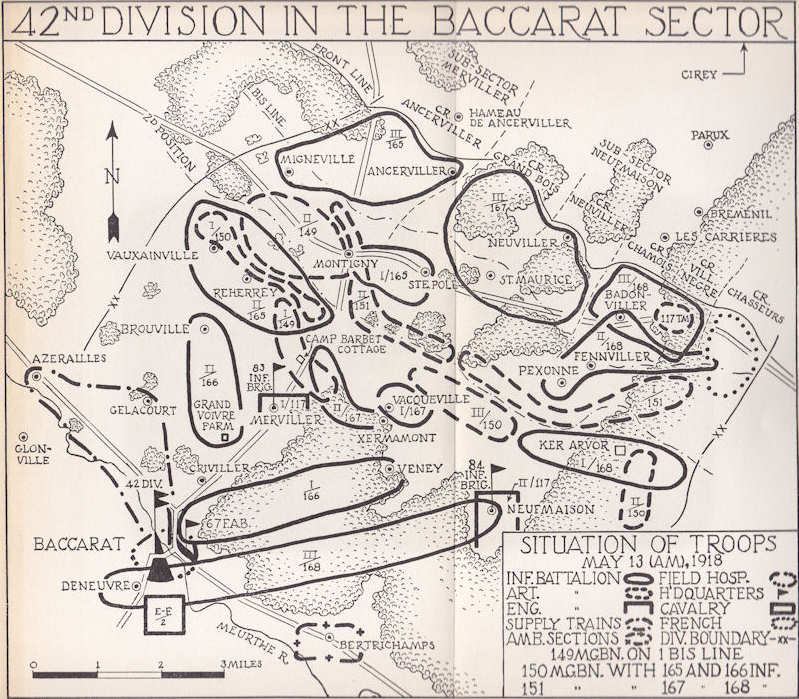

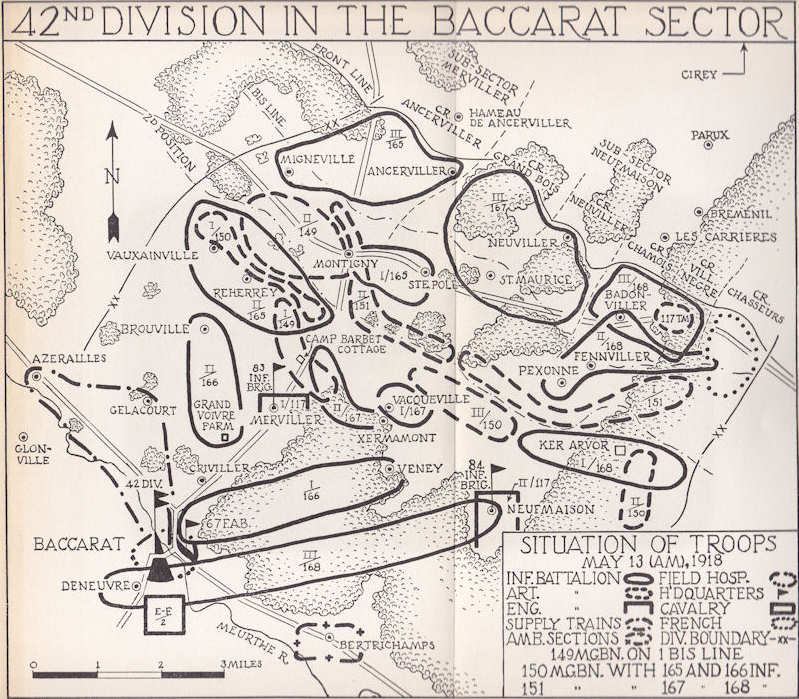

Chapter III - The Rainbow's story begins to be the story

of the war

It was the day before the birthday of George Washington that the Rainbow

Division finished detraining within marching distance of the trenches in the

Luneville Sector - about 10 miles back. The Sixty-seventh Artillery Brigade,

National Guard artillerymen from Indiana, Illinois and Minnesota, had

finished shooting at targets around Coetquidan and had caught up.

Luneville was the "quiet sector” the War Department was telling the people

about back home. Actually there had been no fighting there since 1914, when

the Germans had reached Rambervillers, destroyed the villages and withdrawn.

A rolling, wooded, rich country was this part of Lorraine - altogether too

beautiful to be the scene of battle. And by a sort of tacit agreement both

Germans and French had been sparing the villages; neither side used gas, and

in the day-time a shot was seldom heard.

With the arrival of the Rainbow Division things changed.

They went into the trenches quietly enough. The First Division, when it had

entered the line previously in a nearby sector, had aroused the suspicions

of the Germans and brought down on their own heads a deadly bust of fire,

and a raid in which they had lost prisoners. Profiting by the First's

experience the Rainbow sneaked into position and took up its vigil over

No-Man's-Land in the night without the knowledge of the Germans and without

losing a single man.

But a new foe was facing the Boche in Lorraine - a youthful, eager foe,

confident of his untried strength and impetuous to use it. And he knew there

were a hundred million people back home wondering how he would use it and

how he was getting along. So the Germans were not long without knowledge of

the change in their enemy's order of battle.

It was many weeks later that there went abroad the story about the Germans

who came out of their trench to wash some clothes in a shell-hole in

No-Man's-Land, in full sight of the Americans. It was a true story, and it

happened during the Rainbow Division's first few days in the trenches, and

Alabamians in the 167th Infantry were the heroes of it.

The Germans had washed clothes in that shell-hole before and nothing had

happened. They had known that nothing would happen. On their side the French

had peacefully smoked their pipes in the cool of the evening on the very top

of the trenches. It was simply one of the workings cut of the tacit

agreement.

But a little outpost of Alabamians got one glimpse of this group of Boche in

undershirts arrogantly dipping dirty clothes in the water of No-Man's-Land,

and they opened fire. The Germans scattered like rabbits, some of them

hugging wounds.

A French officer came rushing to the outpost in a fury of excitement. What

did the Americans mean? They had done a terrible thing ! Now the Germans

would be angry and everybody was in for a period of shelling and gas and

raids ! He rebuked the hot-headed Yanks sternly.

"What the hell?" said one of the men later. "I came out here to kill these

Boche, not to sit here and watch 'em wash clothes." But there was justice in

the French officer's rebuke. The Rainbow Division was the pupil of the

French Army. Going into the line it had been divided into small units and

brigaded with four French Divisions of the Seventh French Corps. This is the

way it was divided: The 165th from New York plus two companies of the 150th

Machine-Gun Battalion from Wisconsin were with the 164th French Infantry

Division, with their front line in the Foret de Parroy. The 166th Infantry

from Ohio plus the other two companies of the 150th Machine- Gun Battalion

were in the St. Clement sector with the 14th French Division. The 168th

Infantry from Iowa, 167th from Alabama, and the 151st Machine-Gun Battalion

from Georgia were in the Baccarat sector with the 128th French Division. The

rest of the Rainbow units were distributed along the front of the Seventh

French Corps, where they could be of most use and get the most experience.

The irate French officer had been right, too, in his estimate of the result

of the Alabamians' rashness. The tacit agreement for a kid-glove war in

Lorraine went somewhat to pieces from that moment. The Germans knew now that

new American troops were just across the way. They didn*t have to depend

upon instinct to prove it. They could see the men and the uniforms, just as

our men could see the Germans, so close together were the trenches in some

places. It was enough.

At four o'clock on the morning of March 5 the Boche came over, and the men

of the Rain- bow had their first battle.

For several minutes the German batteries poured a rain of shells on every

trench and every known position from which the Americans might fire back.

They counter-batteried the artillery; their 77s cut the protecting barbed-wire

to pieces. They dropped a barrage behind the trenches to cut off both

retreat and reinforcements. They were certain that all the green Americans

who did not die of fright would be either killed by the fire or captured by

the picked German raiders, who now came across behind the barrage about a

hundred strong with ready bayonets.

The Americans were green - they were not veterans and they didn't act like

veterans. They were horribly scared, too. But they were also at that moment

the most alert and desperate bunch of young Iowans in the world.

The spot toward which the raid was directed was a little group of ruined

brick buildings just north of Badonvillers, known as Le Chamois Farm. The

168th Infantry was holding it. It was right at the junction of two valleys,

an ideal place to sneak upon, but a death trap if properly defended.

What it took to defend it properly the Iowans were all broken out with.

Within one minute after the first alarm they opened up down the valley with

their rifles, the Marylanders cut loose with trench-mortars, and the

Georgians turned on the machine-guns. It was their first chance to fire and

they were as vivacious about it as debutantes at a coming-out ball. The

field artillery, French and American, joined it. Dumbfounded and maddened at

the resistance, the Germans tried to rush the trenches, but they got not

even to the first line. Dawn, breaking slowly through the mist and smoke,

showed three bodies in field-gray hanging grotesquely over the torn wire.

One officer and eighteen men of the Rainbow were killed in this, the first

little battle, and twenty-two wounded. But it was a victory; the raid had

been repulsed. No Man's Land was strewn with German dead.

The spirit of the Division took a great leap. It had discovered for itself

one of the biggest truths the war produced - that the American doughboy

could lick the Boche. Their French comrades were likewise enthused and

reassured. The Rainbow's first batch of Croix de Guerres were awarded for

bravery in this brush.

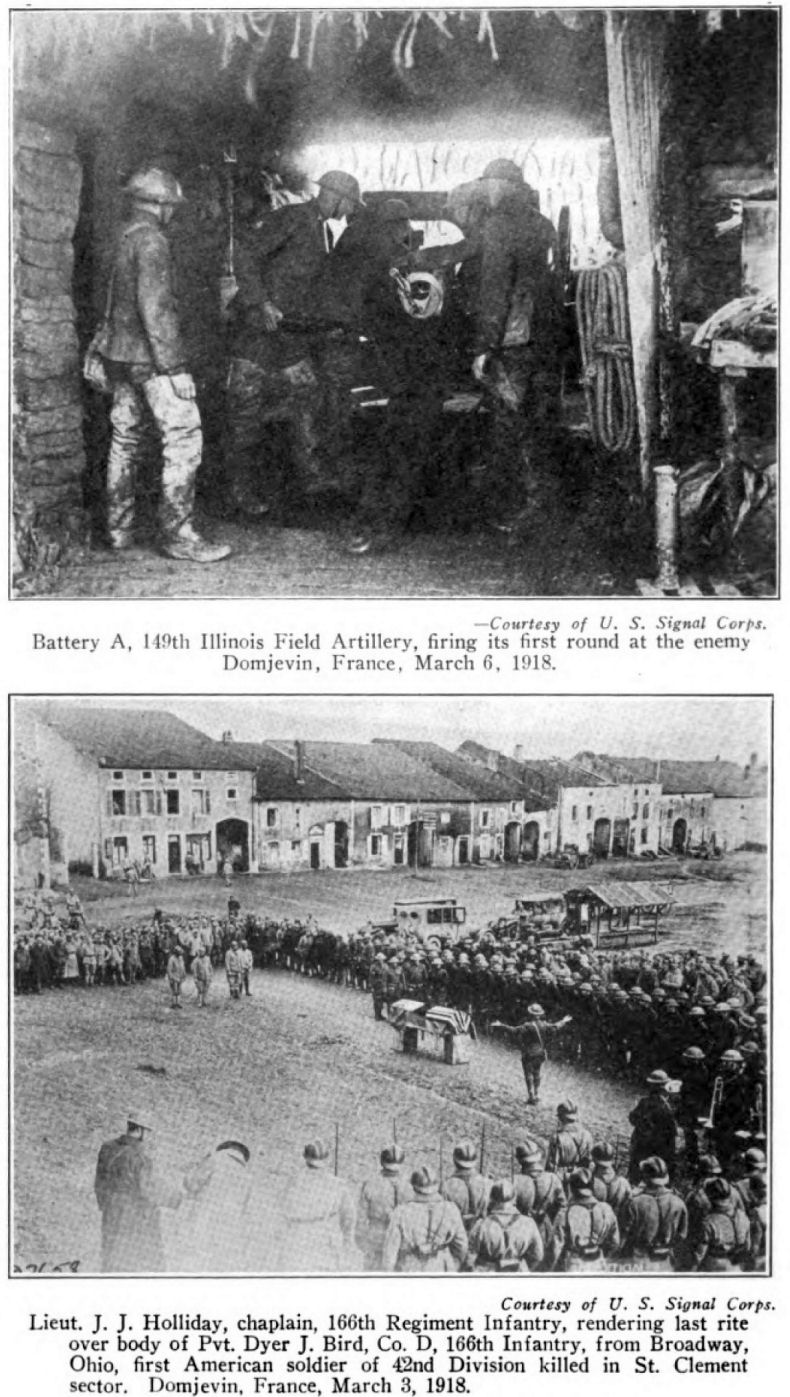

Four days later, March 9, the Rainbow participated in a raiding party of its

own, assisted by the French. For four hours American light and heavy

artillery, trench-artillery and machine-

guns beat upon the German first and second lines, and at five-thirty p. m.

French and American soldiers went over the top together, destroyed the

German shelters, captured a few prisoners, and returned with slight losses.

Colonel Douglas Mac Arthur, the Chief -of -Staff, captured one of these

prisoners. He had gone over the top in a doughboy's uniform and held a Boche

up with his 45. The French gave him the Croix de Guerre for it.

On March 17, in the woods called Rouge Bouquet, in the Foret de Parroy,

immortalized in one of the late Sergeant Joyce Kilmer's poems of the war,

two officers and 50 men from the first battalion of the 165th fought the

Germans out of a strong point and destroyed it. Four New Yorkers were killed,

three wounded, and one reported missing. Twenty Croix de Guerres came to the

165th for that bit of work. They took the Grerman trench and held it, the

first permanent gain ever made by American troops in France.

By this time the Rainbow had been holding a front-line sector for almost a

month. It had earned a rest ; it was ordered to take one. And it has been

suggested since that the title of the Rainbow Division's story ought to be

“Rests We Never Got."

From that time on it never had a rest, as other divisions came to know the

term. Rest after rest ordered for it, but the war always cancelled the

orders. Once, on August 20, it went into intensive training around Bourmont,

south of Neuf-chateau, for ten days, but it didn't rest.

And here, coming out of the Luneville sector on March 20 and being

concentrated by March 28 near Gerbervillers, about 15 miles behind the line,

prepared to march leisurely back to Rolam pont, it got orders to stop.

The great German offensive of March 21 had begun. For two days every German

gun from the North Sea to the Swiss border had fired steadily on towns,

roads, batteries, posts of command. Then had come the news of the German

break-through before Amiens.

The Rainbow Division turned around and marched back to the front, and from

that moment its history is the history of the war.

To begin with, it figured in the complete change of the Allies' military

policy. The menace to Amiens had produced Marshal Foch as Supreme Allied

Commander. General Pershing had made his historic offer to Marshal Foch -

the use of the whole American Army to handle as he wished. All previous

plans were dropped, and in order to release the 128th French Division to go

to the Somme, the Rainbow was ordered to take over the Baccarat Sector. Thus

came to the Rainbow the honor of being the first American division to occupy

a divisional sector all its own, under its own commander. Command of the

Baccarat sector passed to Major-General Menoher on March 81.

All through April there were raids and patrols but nothing unusual happened.

The Germans were not trying to break through here; their effort was

concentrated much further to the north and west, and the Rainbow Division,

with a month of trench vigil already to its credit, was content to take what

rest it could. The weather grew warm and simny, the military out- look on

the Somme improved, the men began to feel at home in the trenches.

They busied themselves improving all the defensive works of the sector, ;and

completing their training. Every man was given an opportunity to become

proficient in his own fighting specialty, whether that was stringing

telephone wires, digging trenches, sniping, hauling ammunition, observing

artillery fire, or cooking army rations. Gradually the Rainbow Division

began to find itself; slowly, with the budding of spring, it began to "feel

its oats," and by the beginning of May it passed that famous point where it

"could be pushed just so fur and no fu'ther," Fights just burst right out of

it.

There was a beautiful little forest called the Bois de Chiens near

Ancerviller. It was full of Boche. They had made an apparently impregnable

position of it, filling it with networks of wire and concrete trenches and

blockhouses concealing minewerfer, machine-guns and the deadly 77's. The

whole thing was covered with dense forest and commanded the open level

ground on three sides.

Into this stronghold, on May 2, French and American artillery poured a

destructive fire. which continued until dusk of the next day. At that time

the Third Battalion of the 166th Infantry, an Ohio regiment, penetrated the

entire salient under command of Major Henderson, with virtually no losses. A

"go-and-come raid," they called it. The raiders found the Forest of Oaks

completely destroyed. Its trenches were filled, all works above ground

leveled, wire entirely torn down, and the forest itself turned into almost a

bare field.

Two mornings later. May 5, Lieut. Cassidy of the 165th led a party over and

sneaked around behind a German outpost at Hameau d'Ancerviller. They jumped

on the Germans, killed two and captured four. Sergeant O'Leary made one

resisting German his own special prize. While O'Leary was killing him with a

trench-knife, Lieut. Cassidy held up two others with his pistol. They

brought the prisoners back across No-Man's-Land under heavy machine-gun fire.

Lieut. Cassidy was made a captain before the war ended, and was twice

wounded. Sergeant O'Leary was killed in battle on the Ourcq.

Three Alabama snipers brought on another mixed fight on May 12, when they

went out in broad daylight to see if their new camouflage suits would

camouflage. They lay in front of a dugout and when Germans began filing out

they began firing as fast as they could load and pull. Almost immediately

the Germans came rushing out in such great numbers that the Alabamians would

have been overwhelmed if they hadn't started a retreat. Two got back safely

; the third was missing.

"Let's go get him I" said the Southerners, so a party of about a dozen went

over the top. They found No-Man's-Land full of Germans waiting for them in

the tall grass. Greatly outnumbered, the Alabamians exchanged shots with

them for a few minutes, and more Germans came out, until there were more

than a hundred. So the rescue party, too, retreated, while one man with an

automatic rifle lay in a shell-hole holding the Germans back from the chase

with a steady stream of bullets. And when the Alabamians got into their own

trenches, instead of one man missing, there were two. The automatic rifleman

hadn't come back.

Two snipers' private little hunting party bade fair now to become a pitched

battle. The blood of the Alabama mountain men was up. Lieut.Breeding, who,

they say, was a full-blooded Indian, gathered nearly a whole platoon and

went out to wipe the Boches up, and bring back both the Americans. Now

crawling, now dashing forward, whooping and yelling as they came, Breeding's

men fell upon the Germans and routed them. Whenever they could they used the

bayonet, and they killed seven Germans and wounded many more, without a

single casualty to themselves.

And they brought back the automatic rifleman, but the missing sniper they

never found.

In his place they brought one dead German, whom they hung over the wire as a

challenge, guarding him constantly until the division came out leaving him

there - a skeleton in rotted, bullet-torn field gray.

Thus the Rainbow again took the "quiet" out of the "quiet sector." The

Germans retaliated with deluges of gas and with raids. On the night of May

26-27, they launched a projector attack on the Village Nègre, northeast of

Badonviller.

Seven hundred gas-shells of large caliber descended all at once and without

warning upon the Rainbow along a front of about four hundred meters. It

caught the Iowa infantry by surprise and the high concentration of deadly

gas killed and disabled two hundred and fifty-one officers and men.

Simultaneously the Boches laid down an artillery barrage and attempted to

raid the trenches, but were repulsed.

Two nights later they tried the same thing, but this time the Rainbow was

ready. It had improved its gas discipline and its losses were only fifty-three

officers and men.

Then came rumors of a great German offen sive in Lorraine. The bivouac of a

battalion of storm troops was discovered on the Rainbow's front and promptly

destroyed by artillery. Defensive works were strengthened and every night

the entire command prepared to receive the attack, determined to beat it

back. But it never came.

Another relief order arrived. Again the Rainbow Division's thoughts were

directed backward

toward the quiet rest area, where it could browse around peacefully for a

few weeks and sleep at night and get cleaned up.

The order was received at division headquarters at Baccarat on June 19. By

June 21 the Rainbow was out of the trenches, leaving the 61st French

Division and the 77th American National Army Division from New York to hold

the Baccarat sector, and it was concentrated between Rambervillers and

Charmes, ready to start again for Rolampont. It had been holding the line

for three full months, and that record for continuous duty was neither

broken nor approached by any other American division throughout the war. At

last (thought everybody) the long-deferred rest was in sight. That, to

repeat, was June 21.

On June 11 the Rainbow Division was entraining, not for Rolampont, but for

another part of the front. The blood-red pen of war history was moving too

fast for American soldiers to rest.

A compter du 31 mars 1818, la 42ème

division sera affectée au secteur de Baccarat jusqu'au 21 juin.

Secteur d'Ancerviller - 2d bataillon du 165ème régiment

d'infanterie - 25 avril 1918

Secteur d'Ancerviller - 2d bataillon du 165ème régiment

d'infanterie - 26 avril 1918

|

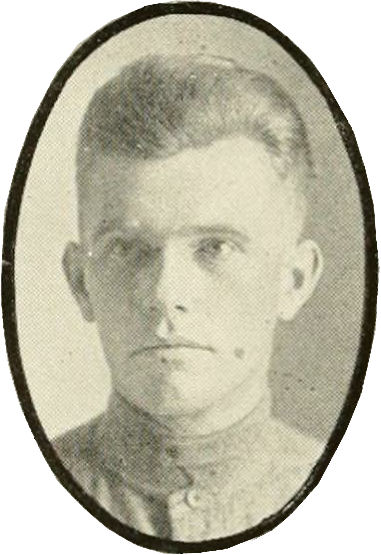

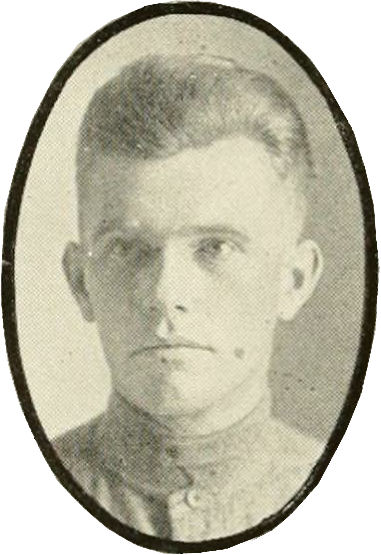

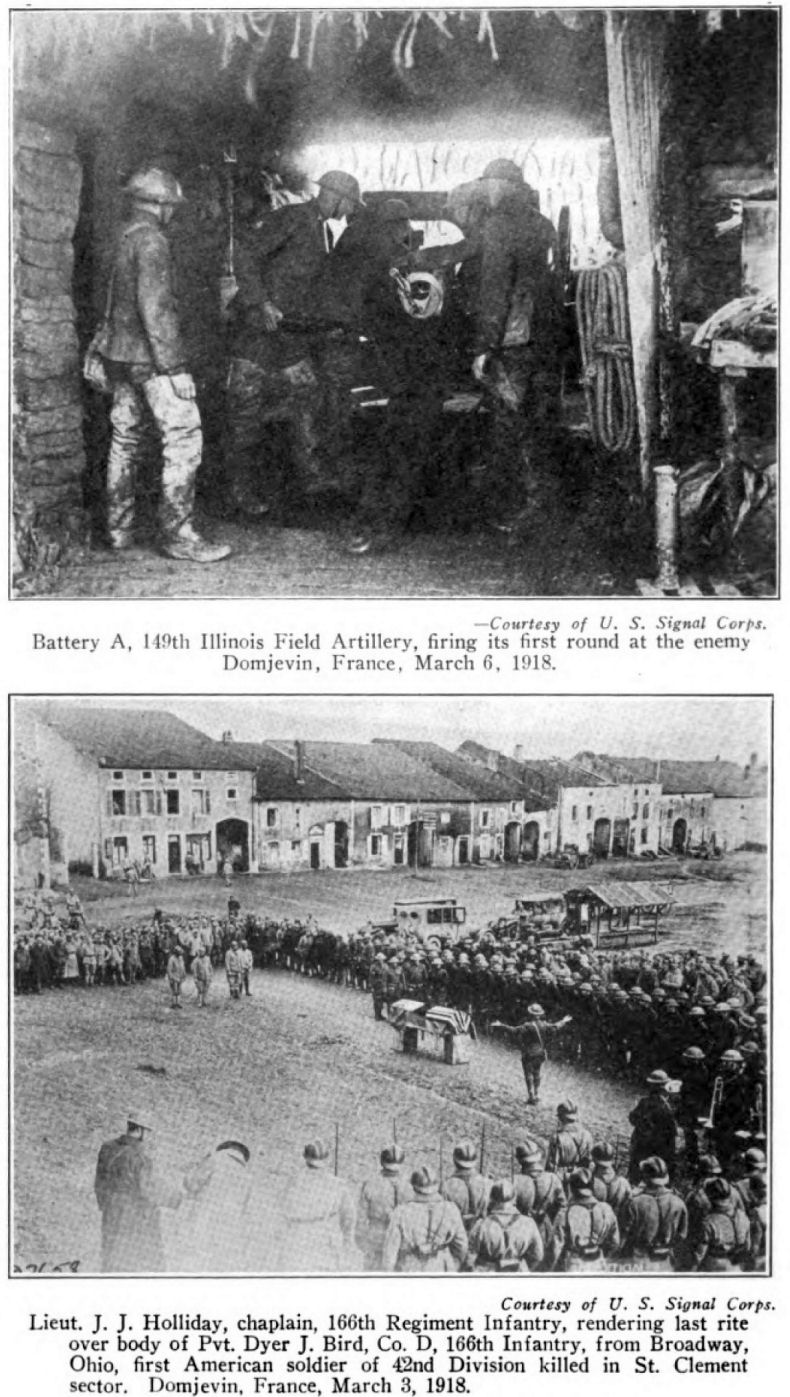

CORPORAL WILLIAM FRANCIS GEHRING

Company A., 149th Machine gun Battalion

Corporal Gehring. son of Mr. and Mrs. John Gehring, 303 High Street,

Hanover, Pennsylvania, was the first Hanover hero to sacrifice his

life on the battlefields in France. He enlisted in the early days of

the war, June 6, 1916, at Reading, Pa. He served seven months with

the 1th Regiment. N. G. P. on the Mexican Border. After being

mustered out his company was again mobilized and he was transferred

to a Machine gun Battalion, Rainbow Division, and was sent to France

soon after. Corporal Gehring was killed March 10, 1918, by shrapnel.

His mother received a letter from Chaplain Halliday which reads in

part as follows: "William was on duty in the trenches and an

exploding shrapnel shell took its toll of his life. On March 11th,

the funeral was held in a village back of the lines in the cemetery

at Domjevin (Meurthe et Moselle), France. Full military honors were

accorded to your son and the grave properly marked."

(York County and the World War - 1920) |

History of the 151st Field Artillery, Rainbow

Division - 1926

µ µ

Rainbow at War - H.J. Reilly - 1936

|

µ

µ